One class of antique firearms misses out on attention – little pocket pistols! Apart from the ‘Queen Anne’ pistols, which were mostly not pocket sized, the bog standard boxlock flintlock and percussion socket pistols are held in scant regard by most collectors, and I’ve yet to find a book dedicated to them. They were, however, probably among the most widely produced and owned firarms of the period – if not the most used. They evolved from the Queen Anne pistol, which had a turn-off barrel screwed onto a breech which was made integral with the lock plate on the right hand side and the floor plate, making a three sided box , with the cock and frizzen spring on the outside of the lock plate side and the trigger pivoting in the floor plate. This arrangement meant that there was still the need for a tumbler on the inside of the lock plate. The box lock came about when it was realised that by moving the cock inside to the centre line, the tumbler could be dispensed with, thus simplifying the design. To support the pivot for the cock another side could be added on the left, and then a slotted top plate to cover the mechanism When used with a conventional trigger, the sear could become part of the trigger, and the bents could be cut in the cock breast, thus reducing the basic lock parts count to cock, trigger, trigger spring and mainspring. the pan had of course moved to the top of the barrel and the frizzen could be mounted directly over the breech. The butt at the back completed the sixth side of the box and enclosed the mainspring. A safety catch was added to anything but the very cheapest boxlocks, either by a sliding trigger guard that locked the trigger(?) or a slider on top of the top plate that both intersected the mainspring and inserted a pin through into the pan cover to prevent it opening. These pistols probably made their appearance around the middle of the 18th century or a bit later. They gained in popularity in cities where street violence was fairly common, including large parts of London during the last quarter of the 18th and first quarter of the 19th centuries. For the most part they were a utilitarian pistol and would have been cheap to make and cheap to buy – almost certainly the vast majority of the more utilitarian – bog standard- pistols would have been turned out in their hundreds by Birmingham gunmakers and engraved, probably as part of the manufacture, with the names of the eventual retailer. It is as unusual to see on engraved ‘Birmingham’ as it is to find one engraved ‘London’ that was actually made in London! Even those that were made in London were probably made from rough forgings made in Birmingham. You will find the names of famous gunmakers engraved on these basic little pistols – some may have been retailed by those makers or given away with their expensive guns, but more often it was just put on by the maker to sell more, mostly when the named maker had left the trade.. Here its important to note the way that the Birmingham gunmaking trade was organised as a whole raft of separate independent craftsmen, each making one or two parts of the pistol and nothing else – the ‘gunmaker was the name given to the organiser of the enterprise who may or may not have had a role in physically making the pistol, but probably not. As a result of the volumes produced, the raw forgings and manufactured parts from Birmingham were usually much cheaper than could be produced in London.

There were variations on the boxlock pocket pistol design, and they came in a variety of sizes and qualities , including some good quality ones that may have been fitted up by good gunmakers, and a few presentation pieces or quality items sold as a cased graniture with other pistols. One early variation was the folding trigger, which reduced the bulk of the pistol considerably and made it more suitable to carry in a pocket or purse at the expense of adding two more parts – a sear that shared the pivot with the trigger, and a spring that acted to close the trigger into the recess in the bottom. Functional variations included ways of adding additional barrels to give better defence capabilities – the most common variety being double barreled pocket pistols with vertically stacked barrels and a tap action to shut off ignition to the bottom barrel while the top barrel was being fired. Extending the number of barrels to three or four by various ingenious means again increase the defensive capability. A further variation combined the tap action with a superimposed charge in a single barrel – the barrel was made in two parts corresponding to the double charge, see below.

Basic functional flintlock turnoff flintlock with the name ‘H Nock’ on the side – Birmingham proof marks. Butt wood a fancy replacement

Basic functional flintlock turnoff flintlock with the name ‘H Nock’ on the side – Birmingham proof marks. Butt wood a fancy replacement

Superimposed load tap action pistol

Superimposed load tap action pistol

Neat decent quality small pocket pistols of the ‘cap guard’ variety, sometimes called ‘top hat pistols – W & S Rooke

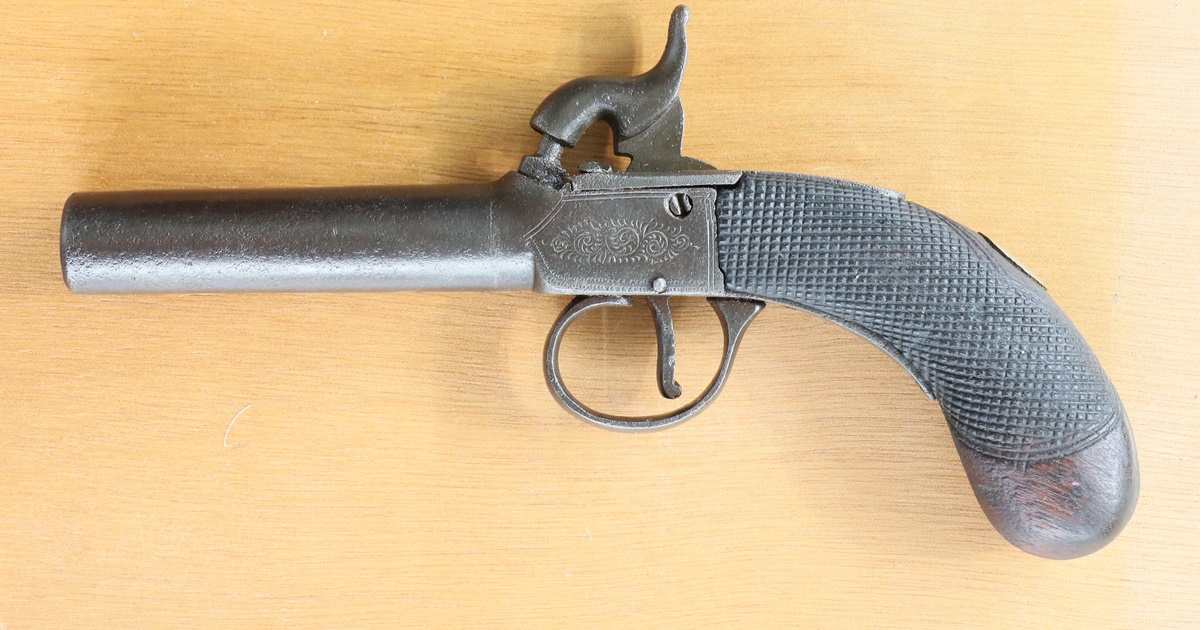

Still pretty basic but omewhat better quality – probably typical of the bulk of Birmingham’s output of pocket pistols. by(?) John Bates

A bit bigger, and a bit better quality too – ( retailed) by Boby of Newmarket

A bit bigger, and a bit better quality too – ( retailed) by Boby of Newmarket

Probably a bit big for a pocket, they have a belt clip, so count as belt pistols – but nice quality by Salmond of Perth

Great article Tim and a nice selection of supporting images.

Pocket pistols are a great way to start collecting antique guns, what’s more, they’re a safer bet for the novice in that you wont fall foul of reconversions etc,

Mind, there are a couple of modern day manufacturues who offer working replicas of some pocket pistols so if in doubt, check the proof marks.

Hi Nick,

Thanks – you are right about the modern replicas, and you could find yourself with an unlicensed firearms and all the trouble that leads to! To be kept without a firearms certificate a pistol must be a) a muzzle loader made before September 1939.

b) a replica of a gun that was in use in 1877, and which cannot readily be converted to fire using normal houshold tools.

Tim

To clean the guns after firing, what is the best approach to remove the barrel? Or is it just best to remove the stock to protect the wood from water damage. Thanks.

If its not too difficult, removing the barrels is a good start, but mostly it is not possible without risking damage – most turn off pocket pistols I see have vice marks in the metal!

I wouldn’t remove the butts as the fixings don’t stand a lot of use, if you can get them out anyway. I would flush out the barrel with a big syringe while the pistol is muzzle down, then clean the rest with a damp cloth followed by lots of spray cleaner/lub. They were not really designed for repeated use, and easy cleaning wasn’t high up the desireable characteristics in the design brief!